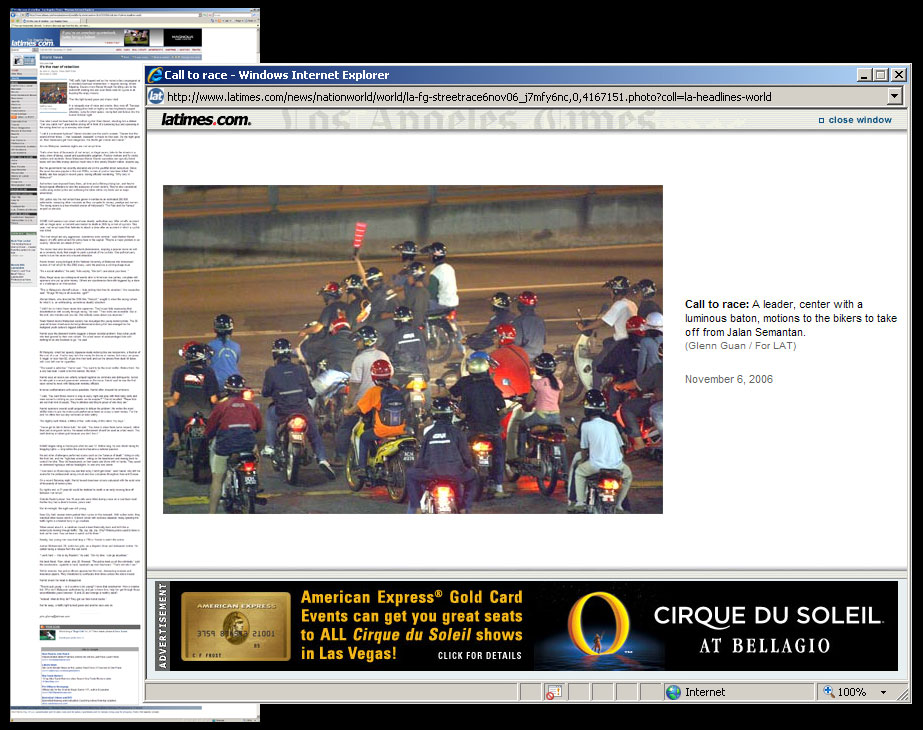

Los Angeles Times, 6 Nov, 2006 THE traffic light lingered red as the motorcycles congregated at a crowded downtown intersection — engines revving, drivers fidgeting. Dozens more filtered through the idling cars to the makeshift starting line and soon there were 60 cycles in all, buzzing like angry insects. Then the light turned green and chaos ruled. In a renegade roar of noise and smoke, they were off. Teenage girls riding pillion held on tightly as their boyfriends popped wheelies, vying for show space, racing fast and furious into the humid October night. One rider turned his head back to confront cyclist Wazi Hamid, shooting him a defiant "Can you catch me?" glare before slicing left in front of a lumbering bus and careening in the wrong direction up a one-way side street. "I call it a motorized typhoon!" Hamid shouted over the wind's scream. "Racers love the sound of their bikes — that 'waaaaah, waaaaah!' is music to their ears. As the night goes on, their maneuvers get more dangerous, the stunts get crazier and crazier." Across Malaysia, weekend nights are mat rempit time. That's when tens of thousands of mat rempit, or illegal racers, take to the streets in a noisy show of daring, speed and questionable judgment. Factory workers and fry cooks, soldiers and students, these Malaysian Marlon Brando wannabes are typically bored teens with too little money and too much time in this orderly Muslim nation, experts say. But the government has recently declared war on the youthful street subculture. Since the races became popular in the mid-1990s, scores of youths have been killed. The fatality rate has surged in recent years, leaving officials wondering, "Why only in Malaysia?" Authorities have imposed heavy fines, jail time and a lifelong driving ban, and they've forced repeat offenders to view the autopsies of crash victims. They've also considered confiscating motorcycles and outlawing the bikes within city limits and at major universities. Still, police say the mat rempit have grown in number to an estimated 200,000 nationwide, menacing other motorists as they compete for money, prestige and women. The racing scene is a two-wheeled version of Hollywood's "The Fast and the Furious" amped on steroids.

SOME thrill seekers turn violent and even deadly, authorities say. After a traffic accident with an illegal racer, a motorist was beaten to death in 2005 by a mob of cyclists. This year, mat rempit used their helmets to attack a driver after an accident in which a cyclist was killed. "The mat rempit are very aggressive, sometimes even criminal," said Shafien Mamat, deputy of traffic enforcement for police here in the capital. "They're a major problem in our country. Motorists are afraid of them." The racers have also become a cultural phenomenon, inspiring a popular movie as well as a university study that sought to paint a portrait of the cyclists. One political party wants to turn the races into a tourist attraction. Rozmi Ismail, a psychologist at the National University of Malaysia who interviewed scores of mat rempit for the 2002 study, calls the practice a coming-of-age ritual. "It's a social rebellion," he said, "kids saying, 'We don't care about your laws.' " Many illegal races are underground events akin to American rave parties, complete with sponsors who put up prize money. Others are spontaneous face-offs triggered by a stare or a challenge at an intersection. "This is Malaysia's showoff culture — kids risking their lives for attention," the researcher said. "At age 18 they're all invincible, right?" Ahmad Idham, who directed the 2006 film "Remp-It," sought to show the racing culture for what it is: an exhilarating, sometimes deadly sideshow. "I didn't try to make these racers into supermen. They're just kids expressing their dissatisfaction with society through racing," he said. "Their skills are incredible. But in the end, one mistake and you die. And nobody cares about you anymore." Wazi Hamid insists Malaysian society has misjudged the young motorcyclists. The 35-year-old former street-racer-turned-professional-motorcyclist has emerged as the maligned youth culture's biggest defender. Hamid says the daredevil stunts suggest a deeper societal problem: blue-collar youth who feel ignored by their own culture. "It's a last resort of underprivileged kids with nothing to do and nowhere to go," he said.

IN Malaysia, small but speedy Japanese-made motorcycles are inexpensive, a fraction of the cost of a car. Youths may lack the money for discos or movies, but many can pump 5 ringgit, or less than $2, of gas into their tank and run the streets from dusk till dawn, with cash left over for cigarettes. "The speed is addictive," Hamid said. "You want to be the most skillful. Riders think: 'I'm a very bad man. I want to be the bravest, the best.' " Hamid says all racers are unfairly lumped together as criminals and delinquents. Invited to take part in a recent government seminar on the issue, Hamid said he was the first racer asked to meet with Malaysian ministry officials. In tense confrontations with police panelists, Hamid often showed his emotions. "I said, 'You want these racers to stay in every night and play with their baby dolls and wear women's clothing so your streets can be emptier?' " Hamid recalled. "These kids are not that kind of people. They're athletes and they're proud of who they are." Hamid sponsors several youth programs to defuse the problem: He invites the most skillful riders to join his motorcycle performance team as a way to earn money. For the rest, he offers free two-day seminars on bike safety. The slightly built Hamid, a father of four, calls many of the riders "my boys." "You've got to talk to these kids," he said. "You have to show them some respect, rather than just strong-arm tactics. Increased enforcement should be used as a last resort. You can't destroy a culture just because you don't like it."

HAMID began riding a motorcycle when he was 12. Before long, he was street racing for bragging rights — long before the practice became a national passion. He and other challengers performed stunts such as the "balance of death," riding on only the front tire, and the "highchair wheelie," sitting on the handlebars and leaning back to control the bike. They did headstands on their seats and drove with no hands. They raced on darkened highways without headlights, to see who was braver. "I look back on those days now and feel lucky I didn't get killed," said Hamid, who left the scene for the professional racing circuit and now competes throughout Asia and Europe. On a recent Saturday night, Hamid toured downtown streets saturated with the acrid odor of thousands of motorcycles. By night's end, a 21-year-old would be stabbed to death in an early-morning face-off between mat rempit. Outside Kuala Lumpur, two 15-year-olds were killed during a race on a rural back road. Neither boy had a driver's license, police said. But at midnight, the night was still young. Near City Hall, several riders parked their cycles on the sidewalk. With sullen looks, they watched other racers storm a 10-block circuit with reckless abandon, many ignoring the traffic lights in a heated hurry to go nowhere. When asked about it, a cabdriver moved a hand frantically back and forth like a motorcycle moving through traffic: "Zip, zip, zip, zip. Why? Motorcyclists used to have to look out for cars. Now we have to watch out for them." Nearby, two young men slouched atop a 110-cc Honda to watch the action. Joehan Mohammed, 20, works two jobs, as a dispatch driver and restaurant worker. He called racing a release from the real world. "I work hard — this is my freedom," he said. "On my bike, I can go anywhere." His best friend, Wan Johari, also 20, frowned. "The police treat us all like criminals," said the woodworker, cigarette in hand, baseball cap worn backward. "That's not who I am." Within minutes, two police officers approached the men, demanding licenses and insurance papers. They threatened to confiscate their bikes unless the riders moved. Hamid shook his head in disapproval. "They're just young — is it a crime to be young? I know that woodworker. He's a creative kid. Why don't Malaysian authorities try and get to know him, help him get through those uncomfortable years between 18 and 25 and emerge a healthy adult? "Instead, what do they do? They get out their ticket books." Not far away, a traffic light turned green and another race was on. |